1972: How to hire the wrong coach, by committee

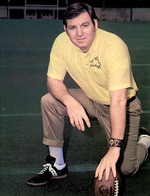

Dick Enright, 1972On February 3, 1972, Dick Enright, 37, an Oregon assistant coach with just two years of college experience under recently departed Jerry Frei, was appointed as the Ducks head football coach.

Dick Enright, 1972On February 3, 1972, Dick Enright, 37, an Oregon assistant coach with just two years of college experience under recently departed Jerry Frei, was appointed as the Ducks head football coach.

Enright signed a one-year contract for $22,500. State regulations only allowed University contractual employees to be hired on annual contracts, but UO Athletic Director Norv Ritchey assured Enright, and the public, that Enright had a “four year commitment.”

Thus ended one of the more bizarre “searches” in the long history of college football at Oregon. Ritchey, who’d blown up the Webfoots football program by publicly supporting Frei while privately refusing to stand up to boosters who insisted on staff changes, had sole control over the hiring process. Soon after Frei’s resignation on January 19, Ritchey had made it clear publicly that Oregon would move “with great haste” to hire a successor.

Privately, Enright was his man.

Norv RitcheyThis was not a completely unreasonable position for Ritchey to take. Although he only had two seasons on the college sidelines, Enright was popular with the players, boosters and local media. As a USC graduate and former high school coach in SoCal, his recruiting contacts were considered solid. And he was the only assistant coach who hadn’t been thrown under the bus by boosters; the rest of the staff, including future college and NFL legends John Robinson, George Seifert and Bruce Snyder, had either already left Eugene or would be gone shortly, having seen what kind of support an Oregon head coach could expect from his boss. If the goal was to maintain continuity in the program, and retain any possible recruiting edge, Enright would have to be considered the logical choice.

Norv RitcheyThis was not a completely unreasonable position for Ritchey to take. Although he only had two seasons on the college sidelines, Enright was popular with the players, boosters and local media. As a USC graduate and former high school coach in SoCal, his recruiting contacts were considered solid. And he was the only assistant coach who hadn’t been thrown under the bus by boosters; the rest of the staff, including future college and NFL legends John Robinson, George Seifert and Bruce Snyder, had either already left Eugene or would be gone shortly, having seen what kind of support an Oregon head coach could expect from his boss. If the goal was to maintain continuity in the program, and retain any possible recruiting edge, Enright would have to be considered the logical choice.

But he wasn’t the only choice. And, as much as he may have wanted to, Ritchey couldn’t just anoint Enright as his new head coach.

The Oregon job was seen as an excellent opportunity, and the vacancy generated national interest. The Ducks were mediocre, but the fans were not yet suffering; even at 5-6, they had been competitive in all but the paycheck games, and Nebraska blew out everyone in 1971. They’d beaten USC in LA for the first time since ‘57, and with a couple of breaks could have been 7-4 instead of 5-6. The program Len Casanova had built over decades was still seen as viable. Autzen Stadium wasn’t even five years old. Frei had recruited solid talent, especially on offense, and Dan Fouts with his superb arm and football mind would be back for one more season. But for all his popularity with the players, and apparent support within the community of boosters, Enright had never been responsible for an entire college football program of any size. It’s a big leap from Gardena High and the CIF to Oregon and the Pac-8.

Ritchey had to justify promoting the least experienced member of Frei’s staff to one of the top 50 or so jobs in all of college football.

And it wouldn’t be a “quiet” hire. There was no shortage of interest in the position, although in many cases the “interest” was in response to a cold call from a reporter asking a question like “Would you be interested in the Oregon job?” Still, a number of reasonably qualified coaches publicly expressed at least a passing curiosity:

- Don Coryell, San Diego State head coach

- Ray Willsey, former Cal head coach

- Chuck Mills, head coach at Utah State

- Dick Coury, head coach at Cal State - Fullerton

- Jack Christiansen, Stanford assistant

- Jim Sweeney, head coach at Washington State

- Spike Hillstrom, Air Force assistant

- Dave Levy, USC assistant

- Carl Selmer, Nebraska assistant

- Bob Schloredt, Washington assistant

- Sam Boghosian, Oregon State assistant

- Claude “Hoot” Gibson, head coach at Tulsa

- Darrell Mudra, former Arizona head coach

No John McKay in the bunch, but no lemons, either. Truthfully, the “interest” from some of these parties was decidedly one-way. (Coryell, the wildly successful coach of the Aztecs who would go on to revolutionize offenses in the NFL – eventually coaching Dan Fouts at San Diego – was taking a wait-and-see approach. “Never in my 11 years of coaching have I applied for a job,” he said, confirming to a reporter that “no, nobody from Oregon has talked to me about it.” ) Still, Ritchey knew he’d be crucified by media and fans alike if he just handed the reins to his hand-picked candidate.

Fortunately for Ritchey, Eugene, in 1972 as in the present day, was a community enamored with the process of process; it seems there has never been a proposal that hasn’t been beaten within an inch of its life, or beyond. And Norv used Eugene’s anal-retentive civic tendencies to his advantage.

For political cover for the “search,” he created an advisory committee. Can you get much more Eugene than that? The committee would interview candidates and then vote on a “recommendation.” To ensure he wouldn’t be accused of complete manipulation, Ritchey stipulated he would ultimately select a coach from the “top two or three” candidates receiving votes from the committee.

The committee had 15 members. Cleverly, Ritchey stuffed the ballot box, naming seven football players to the panel: Dan Fouts, Rick Akerman, Tim Stokes, Greg Specht, Fred Manuel, Keith Davis and Greg Herd. All but Akerman had eligibility remaining; he would be a graduate assistant coach in 1972. In effect, they’d be hiring their own head coach for the upcoming season. Other members were track coach Bill Bowerman; UO vice president Ray Hawk; law professor Wendell Basye; education professor Art Mittman; student body president Iain More and student leaders Mike Marsh, Linda Duke and Charles Carter.

Ritchey had indicated he wanted to get a coach in place quickly. That wasn’t going to happen with committee involvement. But, if it took a fortnight, he was going to get Enright hired.

***

The fortnight:

-

January 19, 1972

Frei resigns.

John Robinson, one of Frei’s assistants who just days earlier had accepted a job with USC, said:

“This is the end.. The people that Cas brought are gone. It will be a different program from here on.”

Ritchey says Oregon will “move with great haste” to hire a successor.

Oregon student body president Iain More blasts Ritchey: “I think if Norv Ritchey had any courage at all, Jerry Frei wouldn’t be in this situation… [Ritchey] should have told them [the boosters] to stuff their money.”

Enright declares his candidacy for the head coaching position, after apparently waiting long enough for the ink to dry on Frei’s resignation letter.

-

January 20

Iain More demands students be allowed to participate in the coaching selection; also calls Ritchey a liar, in a Register-Guard article, an interesting approach towards ingratiating himself with the person who is by policy responsible for selecting the head coach.The Oregon Daily Emerald campus newspaper calls for Ritchey’s resignation:“The University has no room for an Athletic Director who buckles under to outside pressure.”R-G sports editor Blaine Newnham indicates Enright has “gathering support” for his candidacy; in the grand sports columnist tradition, Newnham doesn’t say who the supporters are, other than to say that Frei himself would “most assuredly” back his assistant coach.Paul “Bear” Bryant himself is said to be interested in the Oregon job; the Bear allegedly has an uncle who lives on the coast, and Bear really likes fishing for steelhead. (This rumor is later found to have been mere speculation.) - January 21

Spike Hillstrom, the Air Force defensive coordinator who was a two-year letterman at linebacker for Oregon in the mid-1950s – playing under Frei on the offensive line – throws his hat in the ring. Spike Hillstrom

Spike Hillstrom - January 22

John McKay is pushing one of his assistant coaches, Dave Levy, for the Oregon job:

“As a loyal Oregon alum, I want the best man possible as the next head coach at Oregon.”

(It is worth noting that Enright is a USC alum.)

Ritchey is telling candidates he’s having committee meetings to determine how he’ll determine who he’s going to hire. Dave Levy

Dave Levy - January 23

Ritchey forms his advisory committee; Dick Enright is the first candidate interviewed. - January 24

The committee interviews Spike Hillstrom.

Dick Coury, head coach at Fullerton State, expresses interest in the job.

Carl Selmer, one of Bob Devaney’s top offensive assistants at Nebraska, announces his Carl Selmer candidacy; so does Chuck Mills, head coach at Utah State, who is coming off an 8-3 season. (In an odd twist, Selmer is also a candidate for an assistant job with the Denver Broncos, along with Jerry Frei.)

Carl Selmer candidacy; so does Chuck Mills, head coach at Utah State, who is coming off an 8-3 season. (In an odd twist, Selmer is also a candidate for an assistant job with the Denver Broncos, along with Jerry Frei.)

Jim Sweeney, head coach at Washington State, expresses interest but has not yet applied; this could have been a strategic move on his part, as Sweeney had been seeking a contract extension in Pullman. - January 25

Dave Levy is interviewed.

Claude “Hoot” Gibson, former Oakland Raider star and current head coach at Tulsa, is announced as a candidate. “I’ve never actually sought a job before,” “Hoot” Gibson says Gibson.

“Hoot” Gibson says Gibson. - January 26

The advisory committee, with its heavy active player membership, claims a candidate victim. Sam Boghosian, a coordinator under Dee Andros at OSU who had expressed interest, said he wouldn’t be interviewed by any committee with that makeup.

Darrel “Dr. Victory” Mudra, the head coach at Western Illinois who previously led Arizona, is scheduled for an interview. Unlike Boghosian, he has no issues with the screening committee:The people involved in the committee are the ones you’re generally going to be working with, aren’t they?

Mudra’s record as a head coach: 91-28-2. Darrel Mudra

Darrel Mudra - January 27

Enright tells the R-G’s Newnham the #1 reason he wants the Oregon head coaching job is because “when I started out coaching football I decided to go as far as I could go.” In other words, he wants the job because he wants to be a head coach. (His #2 reason: He recruited twelve of the current players himself; “It’s up to me to look after them.”) - January 28

The committee, having interviewed five candidates, discovers something is missing, but can’t talk about it, other than to say maybe “one or two more candidates” will be interviewed. Chuck Mills and Hoot Gibson will apparently not be interviewed; the new candidates are a mystery, although Enright says that LA Rams assistant coach Larry Weaver had also applied (but also wouldn’t be interviewed). Ritchey now says he doesn’t have any idea when a new coach will be named. “We still want to wrap this thing up as soon as possible, but … I don’t see it happening in the next few days.” - January 29

Jerry Frei is announced as Denver’s new offensive line coach.

Ritchey announces Hoot Gibson will be interviewed after all, on Monday, the sixth candidate to be grilled by committee.

Greg Herd, a burly, gregarious fullback who played under Enright at Gardena High, and a member of the advisory committee, leaves Oregon for Compton JC, to get his grades back in order.

Meanwhile, Enright continues actively recruiting high school players. “Someone has to keep it going,” he comments. - January 30

Bruce Snyder, who coached the offensive backfield under Frei, is hired as offensive coordinator at New Mexico State. Only Enright, DL coach Ron Stratten and freshman coach John Marshall remain from the 1971 staff.

The coaching candidate search is, apparently, over. Meanwhile, on the committee, things are starting to fray at the edges. Another player left the committee; graduate Rick Akerman broke his leg while skiing over the weekend and could not participate in the Gibson interview or the subsequent deliberations. The near equilibrium between players and non-players has tilted towards the nons. On the surface, this would not seem to bode well for Enright, or Ritchey.

And, still, there was something missing from the deliberations… - February 1

A seventh candidate is announced, Joe Gilliam, an assistant coach at Tennessee State. Joe Gilliam

Joe Gilliam

The sad truth was that in 1972, the only black head coaches were at the traditional black colleges in the South. Apparently, it took the committee almost two weeks to discover it had not interviewed an African American candidate — none had even applied for the position. Someone on the committee finally realizes that UO policy at the time required departments to “insure that women and minority group persons have been actively sought out, and, if qualified candidates are identified, that they are encouraged to apply.”

Since the committee had no “minority” candidates, they begin shaking the tree. They cobble up a list of black college football assistant coaches. It’s left to Ritchey to cold-call the “candidates” and arrange the interview logistics.

Gilliam, described in the R-G as “a black,” was the father of future Steelers QB Joe Gilliam Jr. The elder Gilliam had head coaching experience at Kentucky State, and had coached ten years at TSU. Thus “qualified,” Gilliam was offered an interview… if he could figure out how to get from Nashville to Eugene in less than 48 hours. On his nickel. - February 2

Gilliam withdraws his name from consideration:

They insisted on me getting to Eugene and being interviewed by noon today and it just didn’t seem reasonable. I didn’t want to make the trip just so they could have a black coach interviewed…

Joe WadeThe committee covers its EEO bases by interviewing two black coaches who didn’t have to travel cross-country. One is current assistant coach Ron Stratten. The other is Joe Wade, a former OSU player and current head coach at Compton JC. If either coach was humiliated by the process, he did not indicate this publicly.

Joe WadeThe committee covers its EEO bases by interviewing two black coaches who didn’t have to travel cross-country. One is current assistant coach Ron Stratten. The other is Joe Wade, a former OSU player and current head coach at Compton JC. If either coach was humiliated by the process, he did not indicate this publicly. - February 3

With all his bases finally covered, and the advisory committee’s recommendation in hand, Ritchey appoints Dick Enright as head coach of the Oregon football team.

Ron Stratten

Ron Stratten

Stacking the deck hadn’t really helped Ritchey’s cause. It wasn’t athlete support that pushed Enright high enough in the committee’s evaluation to make the final cut. Only three of the remaining five players had him as their top choice; Greg Specht and Fred Manuel had both publicly declared support for Enright, meaning that of the three other returning players on the committee – Fouts, Stokes, and Davis – two of them didn’t want him.

And even Specht had reservations about Enright’s ability to organize a staff. “We know that two years ago, he was coaching in high school.” But he was optimistic.

“Only good can come from Dick’s selection. I think it’s a helluva deal.”

***

Enright had the shortest tenure of any non-wartime Oregon head coach since 1931. After six wins in two years, accompanied by defensive ineptitude and declining attendance, his decision to complain to local media about the team’s coaching facilities was the last straw. He was dismissed in December 1973. He learned of his termination from a reporter via telephone.

His football program having hit rock bottom, and amid suggestions that the Big Sky Conference was more appropriate for Oregon’s athletic efforts, Norv Ritchey resigned as athletic director in 1976, shortly before his last coaching hire, Don Read, was terminated.

The Suffering was well under way.

***

What happened to the other interviewed candidates?

- Claude “Hoot” Gibson returned home from Tulsa to the mountains of North Carolina in 1973, becoming the head coach at D-II Mars Hill College; he retired in 1982. He was recently inducted in the North Carolina Football Hall of Fame.

- Darrell “Dr. Victory” Mudra returned to Western Illinois. In 1974 he was hired at Florida State; he was fired two years later, with a record of 4-18. He later coached at Eastern Illinois, where he won the D-II championship in his first season (1978), and completed his career at Northern Iowa, retiring after 1987. His career record as a head coach was 200-81-4.

- Dave Levy continued coaching at USC until 1980, staying on even after being bypassed for head coach by John Robinson when McKay retired in 1975. In 1980 he moved off the sidelines, becoming assistant AD; but he missed coaching, and joined the San Diego Chargers as an assistant in 1983. Levy became a sort of coaching itinerant ever since, spending nine years with the Detroit Lions, along with stints in NFL Europe, with the CFL Calgary Stampeders, and even a season with the LA XTreme of the late, lamented XFL. In 2005 he returned to his roots, as a 72 year old offensive coordinator and quarterback coach for Harvard-Westlake School in Los Angeles.

- Spike Hillstrom retired from coaching at Air Force in 1977 to enter private business.

- Carl Selmer went to work for the Miami Hurricanes in 1973 as Pete Elliot’s offensive coordinator. Promoted to head coach of a sinking ship with no passengers or cargo in 1975, he was sacked after 1976, with a record of 5-16. He was replaced by Lou Saban.

- Ron Stratten became the first African American head coach at a majority white university in 1972, when he was hired at Portland State to replace Don Read, who joined Enright’s fledgling staff. Stratten led the Vikings through three tumultuous seasons, and resigned after 1974 with a 9-24 record. He became an NCAA investigator, and eventually worked as the NCAA vice president for education services. He retired in 2007.

- Joe Wade was one of Dick Enright’s first hires. He coached the offensive line at Oregon for two seasons, and was promoted to offensive coordinator under Don Read in 1974. That season, during which Oregon set records for offensive ineptitude — with only eight TDs in eleven games — apparently allowed Wade to get coaching out of his system. He resigned prior to spring camp in 1975 to enter private business. Wade spent several decades officiating high school football for the OSAA.

The belated effort by the advisory committee to bring in minority candidates was groundbreaking for its time, but it would be several decades before minority outreach became state policy. In 2009, Governor Kulongoski signed House Bill 3118, which “requires public institutions of higher education to interview qualified minority candidate when hiring head coach or athletic director unless institution was unable to identify qualified minority candidate willing to interview for position.”

benzduck

benzduck

Reader Comments