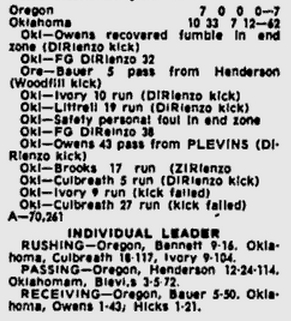

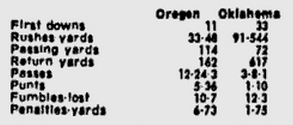

September 1975: Oklahoma 62, Oregon 7

· National News: Trying To Kill The President threatens to replace streaking as the national pastime.

· Oregon’s Bottom Ten ranking, Sept 11: #10 (down from #8)

· This Week’s Game: Oregon vs Oklahoma, in Norman, 9/12/75 1:30pm.

(Some of those team stats are a bit suspect — 617 OU return yards? — but not the important ones.)

***

Many college football coaches will, out of respect or a fear of karma, refuse to say anything before a game to denigrate the quality of the opponent. At Notre Dame, Lou Holtz became legendary for his ability to make it sound like Navy had a chance to beat the Irish. (“Have you theen how Navy runs the ball?”) At Georgia, Vince Dooley would bend over backwards to compliment his weekly non-conference victims, as would Tom Osborne at Nebraska.

Barry Switzer would NOT tolerate that kind of nonsense.

Barry Switzer, 1975. Now that’s a stare.

Barry Switzer, 1975. Now that’s a stare.

Before the first game of 1975, OU coach Switzer complained that it was sometimes hard to get his teams up for games like this, against opponents who were “not the caliber of our football team.” Switzer could be allowed a touch of arrogance: he’d coached the Sooners through 22 games and not lost one.

OU assistant Jerry Pettibone, who would eventually learn the true meaning of epic failure as a HC at Oregon State, commented:

“if we could suit up 120 people, we could hold the score down. But Barry’s pushing [RB Joe] Washington for the Heisman.”

Having finished third in 1974’s Heisman race, behind Archie Griffin and Anthony Davis, Washington certainly had a shot.

The opponent Switzer and Pettibone were alluding to was Oregon, returning to open the 1975 football season for another paycheck, having long since spent the last one they’d earned in Norman for enduring a 68-3 loss.

Oklahoma was merely the defending national champion, ranked #1 in the AP and UPI polls, carried a 20-game win streak, had not lost a game since 1972, and were coming off two years of NCAA probation — sanctions that did nothing to stop the team’s dominance. They graced the cover of Sports Illustrated’s college football preview, in which it was noted that “improving on perfection is difficult.” The Sooners appeared little bothered by the NCAA’s new scholarship and dress-out limits, something that Bear Bryant called “cruel” and sued to prevent.

To quote a local sportswriter:

“The Sooners have more speed than a Harlem pusher.”

(You could write things like that in 1975.)

The Ducks were coming off a 2-9 season, in which they were last in the Pac-8 in scoring and rushing defense, and bore the millstone of an eight game losing streak and an apathetic fan base.

Oregon’s problems were manifold. There had been attrition between seasons; Don Read was not what you would call a “player’s coach”, although he was reportedly beloved by the players who stuck with him. Two of the best players from the ‘74 team, LB Reggie Lewis and RB Rick Kane, had left for San Diego State and San Jose State respectively; Read insisted neither would be missed. Don Reynolds, obviously, would be hard to replace at TB. And the graduation of Norval Turner meant the student section would have to find a new favorite player to boo.

The Pac-8 Skywriters looked at Read’s cupboard and picked Oregon last in the annual pre-season poll.

What can you say about a football team whose starting quarterback has never thrown a varsity pass, whose #1 returning running back gained only 157 yards last season and whose fate is to meet the steamrolling Sooners in two weeks? What can you say? How about good luck and is your Blue Cross paid up?

— Gary Rausch, Long Beach Independent Press-Telegram

This was the team that traveled to Norman on week one to face the Sooners.Injuries during spring and fall camp had taken out the top two QB prospects, Jerry Jurich and Phil Brus, leaving the starting job to Jack Henderson, a sophomore out of Menlo Park who turned 19 in August and, at 6’1 and 185, was considered a bit undersized to be running Read’s veer option attack. The starting and backup centers were injured, and the #3 center, sophomore Fred Quillan, was suffering from a pinched nerve in his neck. Read had benched starting OT Ron Hunt and DT Greg Gibson for violating team rules. RB Eugene Brown, the heir apparent to Don Reynolds, had turf toe and was left home.

Jimmy “The Greek” Snyder generously made Oklahoma a 40 point favorite. He might have been thinking the Sooners were be looking past Oregon to a date with Tony Dorsett and Pitt the following week.

If OU overlooked Oregon, it wasn’t obvious. In a game inexplicably attended by Vice President Nelson A. Rockefeller, the Sooners had covered the 40 pt spread by early in the 3rd period. It is not known whether the Secret Service volunteered protection for the Duck backfield.

Despite Pettitbone’s ersatz Washington-for-Heisman game planning, the Sooner star’s famously hand-painted silver shoes barely saw the field; on a rain-soaked turf, ball control was a challenge, and Oklahoma’s first score came on recovery of a fumble by Mr. Washington in the Oregon end zone, after which he was benched in favor of Horace Ivory.

As can happen in an early-season game during a rainstorm, the game was sloppy. In all, there were 22 fumbles. The Ducks fumbled away the ball on their first two possessions. Still, Oregon trailed only 10-7 after the first quarter, thanks to recovery of a blocked punt — Oklahoma’s only punt of the day — and a toss from Henderson to WR Greg Bauer.

Then the dam broke, the wishbone offense laid waste to the scrawny Duck line, and the final numbers were as ugly as the score. The Sooners scored six times in the 2nd period; four touchdowns, a field goal, and a safety when Oregon was called for a personal foul in its end zone. By the end of the period it was 43-7, and Switzer had pulled every starter and many of his reserves.

Despite fumbling 12 times and losing three of those, Oklahoma still rushed for 544 yards on 91 carries. Oregon suffered ten turnovers, a record, on seven fumbles and three picks.

Read said “That’s the best football team I’ve ever seen.” This presumably included the ‘72 Oklahoma team that stomped Oregon 68-3, when Read was one of Dick Enright’s assistants.

Afterwards, Read praised his team’s fight in somewhat pathetic terms.

“We hit the heck out of them …

The score got a little out of hand in the second quarter…

There’s hope, men, I mean it. There’s hope.”

And Switzer? “Offensively, we didn’t play like we can,” he said. “We’ve got to go back practicing fundamentals and working on basic mechanics.” Right.

**

The Aftermath:

Oklahoma went on to post a 11-1 season, its lossless streak broken in inexplicable fashion by a 23-3 loss at home to a mediocre Kansas team. They still were Big Eight co-champions, finished the season #2, defeated #4 Michigan in the Orange Bowl, and finished the season as undisputed national champions after #1 Ohio State lost in the Rose Bowl to UCLA.

Joe Washington finished fifth in the Heisman race behind Archie Griffin, Ricky Bell, Chuck Muncie and Tony Dorsett. Here’s Joe’s 1975 highlight film.. perhaps the moves of this native of Port Arthur will remind you of another Texas product of more recent vintage:

Joe had a short but productive NFL career with the Colts, Redskins and Chargers, and reached the Pro Bowl in 1979. He’s a member of the College Football Hall of Fame. And OK, it’s not from 1975, but here’s Joe making the greatest 3 yard punt return in history against USC in 1973.

Switzer’s brilliant Oklahoma career ended years later with a thud; he eventually resigned, in 1989, after his lawless and scandal-ridden program made the cover of Sports Illustrated in just about the least flattering way possible. Switzer joined the Dallas Cowboys, won Super Bowl XXX in 1996, and retired from coaching after the ‘97 season.

And Oregon? The next week they opened at home against San Jose State, and none other than running back Rick Kane, who had flunked out of Oregon just six months earlier. (In 1975, you didn’t need to pull a Masoli to change schools without sitting out a year. All you had to do was find a JC that would let you pass 36 credits in one summer session. Apparently, that wasn’t hard to do.) Kane must have greatly enjoyed beating his former team, if only with a field goal and a safety.

New UO president William Boyd was memorably quoted as saying “I’d rather be whipped in a public square than watch a game like that.”

The Ducks finished the 1975 season 3-8, having finally stopped a 14-game losing streak with a win against Utah, a victory in the Palouse, and a 14-7 win in the Civil War — the first CW win in Autzen history — that sent Dee Andros into retirement.

benzduck

benzduck