The Incorruptible Mickey Bruce

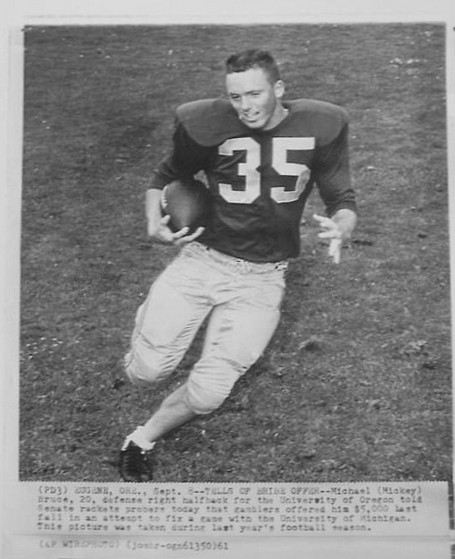

I found this wire service photo of an Oregon defensive back from the early 60s, Michael “Mickey” Bruce, on eBay in 2009. It was listed at $5.99.

Without the caption at the bottom of the photo, this is just another picture of a healthy-looking mid-20th-century football player. Not mentioned in the ebay listing itself, the caption refers to Mickey Bruce being offered $5,000 by two Chicago gamblers to help throw the 1960 Michigan game.

An event that created national headlines and Senate hearings, and ended with a scandal of sorts, along with a first brush with notoriety for a very “interesting” individual, has its 50th anniversary this year.

This is the story of how an Oregon pre-law student fingered a future Hall of Fame gangster in a Senate hearing, then essentially told the legal system to go fly a kite.

***

Len Casanova’s 1960 team was pretty good. With Dave Grayson and Dave Grosz in the backfield, along with a 5’3” (yes, 63-inch) receiver with the perfect name of Cleveland Jones, the Ducks went 7-2-1, with losses at Michigan and to eventual Rose Bowl champ Washington and a tie with OSC; this was good enough to gain a Liberty Bowl invite to play Penn State. Oregon lost the bowl, played amid 2 feet of snow in freezing temperatures in Philadelphia, 41-12, but the biggest news during the season was made during a trip to Ann Arbor to play Michigan early in the year.

On arrival in Dearborn, where the Ducks were staying before the game, a 27 year old Brooklyn schoolteacher named David Budin approached Mickey Bruce, a starting junior halfback/defensive back, in the airport terminal. Bruce said Budin introduced himself as “a friend of Jim Grenadi”, who had played basketball at Oregon and was a friend of Bruce.

According to Bruce, Budin asked him for two tickets for the Michigan game. Bruce said he sold Budin a pair of tickets for $50. (Of the many things football players in 1960 could get away with, selling comped $6 tickets for $50 was one of them.)

Later that day, after Bruce had checked into the team’s hotel, the Dearborn Inn, Bruce said he was approached by Budin and two other men, identified as “Frank” and “Bobby”. Bruce said he was told he could earn $5,000 if he “let a pass receiver in behind him”, and influence Oregon QB Dave Grosz to “call the wrong plays.” They told him to meet them at their room at the Dearborn Inn to finalize the deal on Saturday morning before going to the stadium with the team.

No fool — his father was a Chicago attorney — Bruce said thanks but no thanks, and told Len Casanova about the conversation. Cas told Oregon AD Leo Harris; Harris called the FBI, who contacted state police. Meanwhile, Cas called an unusual late-night pre-game meeting. Dick Arbuckle, a receiver on the team (and future football coach at Sheldon High), recalled that it was “very unusual.. They told us the situation, asked if any of the rest of us had been approached, and told us to be alert and report any unusual contacts.”

The next day, Michigan state police detectives accompanied Bruce to the gamblers’ hotel room, only to find they had apparently been tipped off — “Frank” and “Bobby” had checked out. The cops hung around long enough to arrest Budin when he showed up, who was probably not all that surprised to see his “friends” had cheesed it.

Bruce proceeded to the Big House, where he did everything but throw the game, playing by all accounts outstanding pass defense, even intercepting a pass and returning it to the 32 yard line. It was as far into Michigan territory the Ducks would get during the game, which they lost 21-0; they had been 6 point underdogs. Cas later recalled the episode shook the team’s focus; the team played miserably, with Grosz overthrowing receivers all day, and in the hot humid conditions the team really didn’t have a chance.

It’s possible that “Frank” and “Bobby” knew that merely attempting to bribe the team might have a negative impact on Oregon’s chances against the spread. All we know is that they got off scot-free this time. As for Budin, without sufficient evidence of a crime, he was charged with registering at the hotel under a false name, and paid a $100 fine.

**

Mickey Bruce had been drawn into what turned out to be a nation-wide scandal. Basketball and football games were being influenced on a wide scale by gambling interests. Eventually, Senator McClellan of Arkansas convened his select committee to investigate gambling in collegiate athletics. A year after the Michigan interaction, Bruce was called to testify before McClellan’s committee.

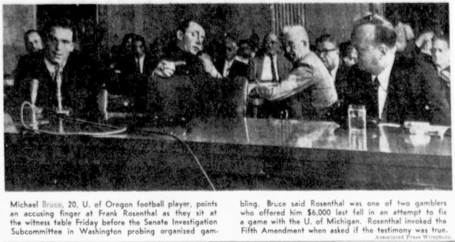

Mickey Bruce fingers Frank Rosenthal, US Senate hearing, 9/8/61

Mickey Bruce fingers Frank Rosenthal, US Senate hearing, 9/8/61

On September 8, 1961, sitting at a Senate hearing witness table with Frank Rosenthal — the “Frank” he’d met at the Dearborn Inn — Bruce, literally, fingered Rosenthal as one of the men who had attempted to bribe him.

Bruce told the senators that Jim Grenadi had asked him to get the tickets for two gambler friends, who wanted to attend a game that they would be betting heavily on. On meeting the gamblers in their hotel room, he learned of their desire that he take a backfield dive. Bruce said he’d “played along”, telling Rosenthal he’d be back later that evening to arrange the deal; instead, Bruce reported the incident to Cas, setting the law in motion.

On Bruce’s return to the gamblers’ hotel room, he testified, he was given $50 for the two $6 tickets, and asked to help ensure the Ducks lost by at least 8 points by playing bad pass defense, and told he’d be given $100 per week for the rest of the season if he’d phone Rosenthal in Miami Beach each Monday and give the gambler reports of injuries on the Oregon team. Rosenthal also offered Bruce a $5,000 bonus if he could bring QB Dave Grosz into the arrangement, for which Grosz would also receive $5,000. Bruce left, and returned to the hotel with detectives the next morning to see Budin being led away in handcuffs.

Rosenthal, as was his right, plead the 5th Amendment.

**

In October 1961, the Wayne County (Michigan) district attorney’s office announced that it wanted Mickey Bruce to come to Detroit and swear out a complaint against the three men who had attempted to bribe him. As Bruce was the only witness to the attempt, without his complaint there would be no prosecution of the gamblers. The Ducks had a game scheduled against Ohio State in mid-November, and the Michigan authorities thought it would be convenient for the team to bring Bruce along so he could file the complaint.

But Bruce was out for the season — he separated a shoulder during a loss to Stanford — and had not planned to make the trip to Columbus.

Cas and Harris urged him to come along. But Bruce now said he wanted to be done with the whole matter. In an interview with the Register-Guard, Bruce said “as far as I’m concerned, this whole thing should have been dead a month after it happened.” He had conferred with his father, the Chicago attorney, and concluded that he could not be compelled to swear out a complaint. He said he didn’t have time to go — he was president of his fraternity, immersed in study, and just didn’t want to take the time to travel cross-country. In his opinion the Michigan police had botched the whole situation from the start. He didn’t want to have any more to do with what he considered a poorly run prosecution that had little chance of success. And it had been so long, he wasn’t sure he remembered everything correctly; it was “a little hazy.. as to who said what.”

In refusing to go along, Bruce stood up to AD Leo Harris, who had assured the Michigan DA that Bruce would be available for “interrogation.” But Mickey Bruce was tired of the whole thing, of the “taken any bribes lately?” jokes, and wanted to get on with his life. Harris even appealed to Oregon prexy Arthur Flemming, who said that although it would be nice if Bruce would go, Flemming certainly couldn’t force him to do so.

And that was that. Bruce stayed home, Oregon went to Columbus and lost to the Buckeyes 23-12, and the Wayne County DA dropped the case against Budin and Rosenthal for lack of evidence.

***

Frank Rosenthal and David Budin were eventually indicted by a North Carolina grand jury in 1962, charged with offering a $500 bribe to a NYU basketball player to shave points at a NCAA tournament game against West Virginia in 1960. They plead no contest; Rosenthal paid a $6,000 fine, and Budin received two years probation.

Does the name Frank Rosenthal ring a bell yet?

Does the name Frank Rosenthal ring a bell yet?

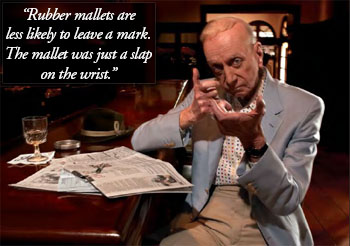

It should. He was credited with inventing the sports book industry in Las Vegas, and was called the “greatest living expert on sports gambling” by Sports Illustrated.

The colorful life of Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal, who died in 2008, was the inspiration for Martin Scorcese’s movie “Casino”. Rosenthal was played by Robert DeNiro.

There’s a great obitorial on the Las Vegas Review-Journal’s web site.

Frank Rosenthal, who died in 2008, was not a good person.

“It’s been said you should never speak ill of the dead. There are exceptions to the rule. Frank Rosenthal is one of those exceptions. He was an awful human being.”

— former federal prosecutor in Las Vegas

The football history of Mickey Bruce ends with that Register-Guard interview. The ‘61 Stanford game was his last appearance in an Oregon uniform. That injury-shortened senior year dampened his career statistics; in three seasons at Oregon, he rushed 29 times for 128 yards and one TD, and caught 10 passes for 113 yards and 3 TDs. Defensively, he intercepted six passes in that fateful 1960 season, and returned 6 punts for an 11 yard average. Bruce was drafted in the 24th round of the ‘62 AFL draft by the Oakland Raiders, but did not pursue a professional football career.

As we expect of the great Ducks, Michael J. Bruce’s story goes beyond the gridiron. He is on that short list of individuals who have implicated gangsters and not only survived, but prospered under their own good name. In 1981, Mickey Bruce received the UO Leo Harris Award, presented to an alumnus letterman who has been out of college for twenty years and who has demonstrated continued service and leadership to the university. Other Harris winners include Bill Dellinger, Dan Fouts, Tinker Hatfield, Alberto Salazar, Dave Wilcox, Ahmad Rashad and John Robinson.

That’s a much better lifetime achievement award than a car bomb.

benzduck

benzduck

Michael J. “Mickey” Bruce died March 27 of cancer at his home in Oroville, California. No services are planned per Mickey’s request.

oregon football history in

oregon football history in  Heroes,

Heroes,  Player profile

Player profile